Over the Edge (a Jonathan Tweet RPG) includes a three-column essay by Robin Laws, “The Literary Edge” (at pp 1912-93 of my 20th Anniversary edition).

The closest analogue to role-playing is improvised theatre, in which actors invent scenes as they go along. Participants must be receptive to contributions of others and use their own input to build on them. The Prime Directive of the improviser is “never negate,” which means that the actors must accept all ideas as they come up and work with them.

In role-playing, however, the GM is often called on to say “no” to players’ desires for their characters; this is because roleplaying games are ongoing epics centred around the adventure genre rather than brief comedy skits. The GM is responsible for decisions about characters’ successes in the physical world, and will often decide that attempts at given actions fail. After all, stories in which the leads breeze over every obstacle without opposition are undramatic and therefore fail to entertain.

But GMs should also be prepared to say “yes” to players when a suggestion inspires new possibilities for the storyline. In fact, a good GM will work to incorporate player input into his plans. In drama, character is the most important thing, and this element belongs to the players. The GM is not a movie director, able to order actors to interpret a script a given way. Instead, he should be seeking ways to challenge PCs, to use plot developments to highlight aspects of their character, in hopes of being challenged in return. . . .

When viewing role-playing as an art form, rather than a game, it becomes less important to keep from the players things their characters wouldn’t know. When character separate, you can “cut” back and forth between scenes involving different characters, making each PC the focus of his own individual sub-plot. This technique has several benefits. First, it allows players to develop characters toward their own goals without having to subsume them to the demands of the “party” as a whole. Secondly, it quickens the pace, allowing players to think while their characters are “off-screen,” cutting down on dead time in which players thrash over decisions. . . . Finally, this device is entertaining for players out of the spotlight, allowing them to sit back and enjoy the adventures of others’ characters.

The price of this is allowing players access to information know to PCs other than their own. But it’s simple enough to rule out of play any actions they attempt based on forbidden knowledge. This doesn’t mean there will be any shortage of mystery. Any OTE GM will still have secrets to spare. In fact, by allowing the number of sub-plots to increase, the GM is introducing even more questions the players will look forward to seeing answered.

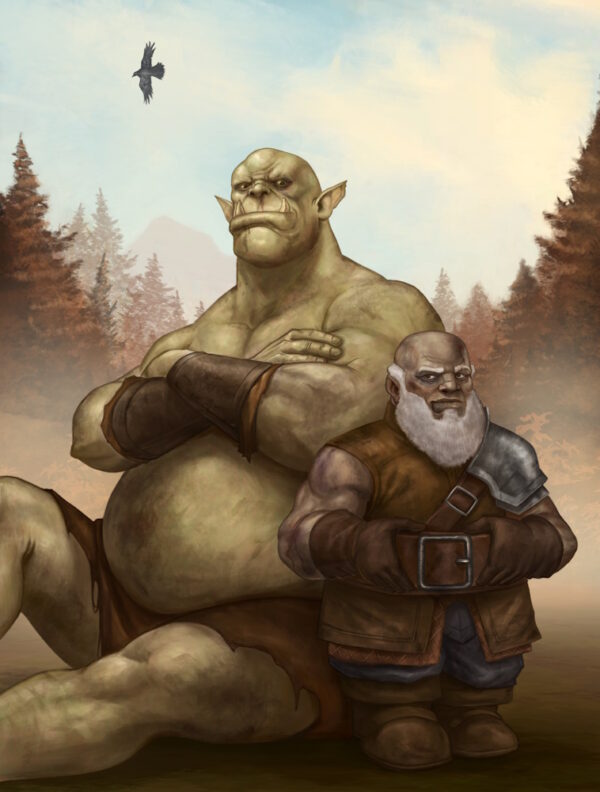

GMs who employ this multi-plotting device will find it changes the nature of PC interaction, making meetings between them more remarkable and meaningful as they become rarer. Now PCs will interact because they want to for reasons arising from the story, not merely because they have to as part of a team. After all, parties of adventurers in roleplaying sessions are often made up of wildly disparate types who would never ally with each other, except for reasons outside the storyline: the players all want to be included, and the GM has one plotline prepared, so they all get shoehorned together. . . .

For years, role-players have been simulating fictional narratives the way wargamers recreate historical military engagements. They’ve been making spontaneous, democratized art for their own consumption, even if they haven’t seen it in these terms. Making the artistry conscious is a liberating act, making it easier to emulate the classic tales that inspire us. Have fun with it, and enjoy your special role in aesthetics history – it’s not everybody who gets to be a pioneer in the development of a new art form.

– the spontaneous creation and performance – rather than the authorship of rules, settings etc.